An Antidote to Device Dependency? The Nature Prescription

One of the most common symptoms of Cultural Stress is device dependency. This can be described as a need to check one’s phone repeatedly for incoming messages, email, or social media posts—and to feel a sense of anxiety if that need is thwarted.

The problem is particularly acute among young people. For example, a 2012 study found that young adults aged 18–24 send an average of 110 text messages per day, or roughly 3,200 texts each month. The average study participant also checked his or her cell phone 60 times a day.

If that weren’t enough digital dependency, many people use their phone as an alarm clock, sleeping with it next to their bed. Many also use it as a pedometer, plus radio or CD player, maintaining their connection while exercising. Although this type of cell phone attachment may give users the impression that they are constantly connected to the world and therefore less alone, the reality is not as comforting.

Like any other addiction, too much dependency on our digital devices has debilitating consequences. Texting and driving is a deadly one. Osteopaths and chiropractors warn us of “forward head syndrome,” or “iHunch.” And a growing body of research suggests that digital dependency has deleterious mental health consequences, as well. A U.S. study found that participants who were temporarily separated from their cell phones performed worse on cognitive tasks due to physiological symptoms similar to drug “withdrawal,” such as increased heart rate and blood pressure accompanied by feelings of anxiety. Participants also reported feeling a sense of loss, or a diminishing, of their extended self—their phones.

Worse, two national surveys of U.S. adolescents in grades 8 through 12, showed an alarming increase in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates since 2010, especially among females. Though causality has not been determined, the increase correlates closely with time spent on new media, including social media and electronic devices such as smartphones. (In contrast, adolescents who spent more time on non-digitally mediated activities, such as face-to-face social interactions, sports, homework, print media, and participation in religious services reported fewer depressive symptoms.)

Of course, one of the major differences between device-mediated interaction and face-to-face social interaction is that one is “curated,” e.g., selectively edited, while the other is not. As one researcher said, “The comparisons that are implicit in looking at other people’s lives online, which are often highly manicured (and misleading), are thought to be what’s so depressing about social media.”

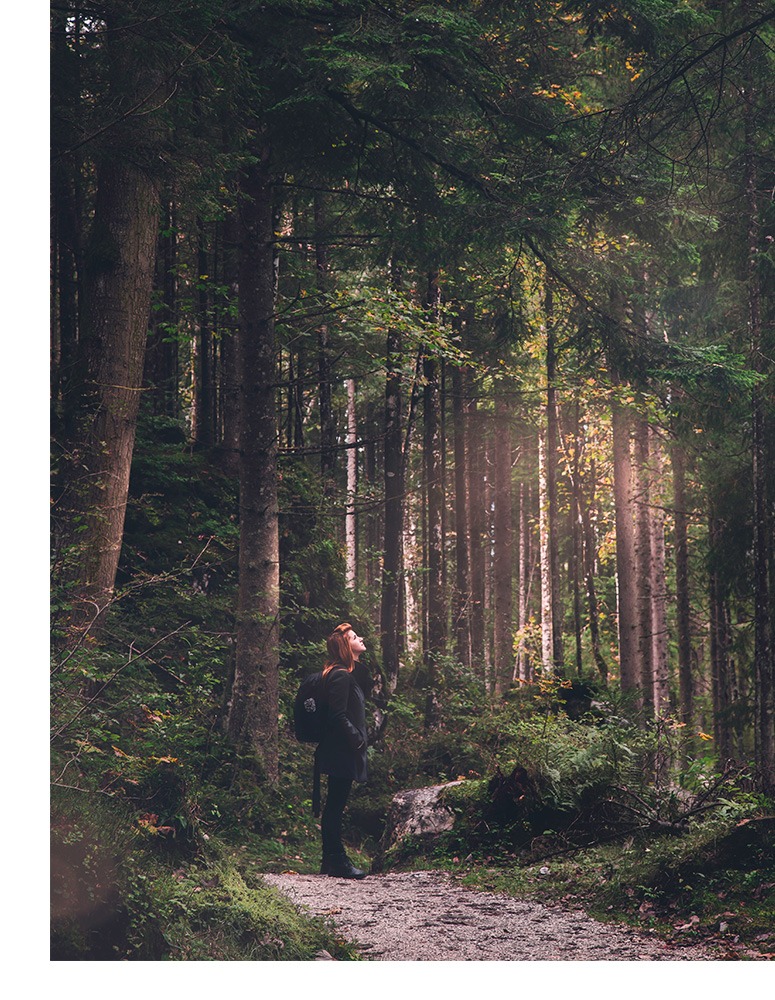

The bottom line is that virtual reality is not reality. Fortunately, the antidote is as near as your front door. The effects of sunlight, fresh air, and interaction with natural surroundings are well-established. And you don’t have to disappear into the wilderness to enjoy the benefits. Walking barefoot in the grass or a sandy beach is, literally, grounding. Eating your lunch on a bench outside, having dinner with friends or family on the patio, or taking a 10-minute walk in a park will suffice. Hospital patients even recover more rapidly when their room looks out upon a garden or bit of greenery.

At Murad, we launched an “EyesUp” campaign (see video below) to encourage people to look up from their devices and interact with the real world around them. That included noticing the weather, seeing the sky, speaking to passersby, and being fully present for their lives. It turns out that lifting one’s eyes also lifts one’s mood. Consequently, a growing number of physicians are literally writing prescriptions for time spent in nature. They have found that general advice like, “Get outdoors, exercise,” is too often ignored, while writing specific instructions like, “Spend 20 minutes in the park” (or the woods, or the beach, or tending your garden), is more likely to be followed. In Japan, “forest bathing” is a recognized prescription: being surrounded by the sights, sounds, colors, and calm of a forest is soothing for both mind and body, slowing heart rate and blood pressure and boosting the immune system. Forest-bathing’s primary proponent, Dr. Qing Li, makes the point that this is not exercising; it is unplugging, slowing down, and decompressing.

As a dermatologist, I know that healthy skin is a direct reflection of how we live our lives. The irony of our time is that, while we are more digitally connected than ever before, we are often more socially isolated. We are also cut off from the natural world, which has nurtured human beings through all of history. Fortunately, the power to address this resides where it always has: within us. Make it a practice to spend at least part of one day a week unplugged and in nature. You’ll live longer, healthier, and happier for it.